|

| Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) |

The Qing Dynasty 1644 - 1911 AD

About the Qing

Much weakened by long wars with the Mongols and harassment by Japan, the Ming dynasty was brought to a close in 1644 by the Manchu chieftains. To prevent internal conflict, the Qing pursued in certain circumstances a policy of giving rewards of land for cultivation and reducing or exempting taxes. The early Qing emperors, especially Kangxi (1662-1722 ), Yongzheng (1723-35) and Qianlong (1736-96), not only resolved the long conflict between nomads and peasants which had plagued China throughout its history, but also undertook a series of measures to develop the economy, culture and transportation in the frontier areas. As a result, they consolidated national unification and laid the foundation for modern China's territorial boundaries.

|

| Map of Qing Dynasty |

In spite of these noticeable achievements, the Qing rulers were autocratic and despotic. The nation was still agriculturally based and dominated by feudal ethics and rites. Worse still, the Qing empire in its relationship with foreign countries was isolationist, conservative and arrogant. It paled in comparison with the newly industrialized West and was left behind in world development. The gap between China and the West gradually widened.

During the mid-Qing dynasty, social conflict began to surface. Many revolts took place and that of the White Lotus Sect put an end to the Qing's golden age. The Opium War of 1840 and increasing foreign aggression resulted in many unequal treaties being signed between the Qing and Western imperialist powers. All these treaties demanded that China cede territories, pay indemnities and/or open trading ports. Eventually, China became a semi-feudal and semi-colonized country. With its corrupt politics and conservatism, the Qing dynasty rapidly declined. The dynasty was finally overthrown by the Revolution of 1911 led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen.

Ye Gui (1667-1746) |

Further Development on Febrile Disease

In the Ming dynasty, Wu Youxing's Weiyilun (On Pestilence) of 1642 exerted considerable influence on what is known as the "school of febrile illness" (wenbing). Wenrebing which was derived from "wenbing", were diseases associated with heat, which today remains one of the disease causing agents of TCM. Through clinical practice and further study, physicians in the Qing dynasty gave new prominence to the study of wenbing. The most significant representatives of this school included Ye Gui , Xue Xue and Wu Tang. Wang Mengying (1808-66) devoted an entire work to fever-related illnesses, the Wenre Jingwe. Wenre Fengyuan (The Source of Fevers) by Liu Baoyi (1842-1901) and Shibinglun (Seasonal Illnesses) by Lei Feng in 1882 also exerted a lasting influence in this area.

Confronted by the challenge of Western medicine, the practice of Chinese medicine was buttressed by its long-held traditions and continued unabated in the later-Qing period. Its survival was assured by the adherents to the Shanghanlun (Treatise on Febrile Diseases), school of "cooling", the Shennong Bencaojing (Classic of Herbal Medicine) and other champions of traditional Chinese medicine.

New Anatomy

Chinese anatomy continued to rely essentially on the information provided in the Huang Di Nei Jing (The Yellow Emperor's Medicine Classic). Little had been added to this work since its completion because surgery had not been looked upon favorably over the centuries.

Wang Qingren (1768-1831) |

Although it was not the first documentation of proper anatomy, Wang Qingren (1768-1831) published his Yilin Gaicuo (Errors Corrected from the Forest of Physicians) in 1830. In this, he dispelled certain long-held beliefs, such as the claim that urine originated from excrement and that the lungs had 24 holes. His observations from corpses abandoned in public cemeteries and execution grounds led him to discover organs and structures previously unmentioned in traditional Chinese medicine. These included the abdominal aorta, pancreas and diaphragm. He also showed that it was the brain and not the heart, as was previously thought, that was the seat of thought and memory.

|

Use of the Smallpox Virus to Combat Smallpox

Prevention measures for variola (smallpox) had been used in China as early as the sixteenth century, during the time of the Ming. According to Yu Maokun, whose Douke Jinjing Fujijie was published in 1727, variolation (inoculation against smallpox) had been practiced since the years 1567-72. The method involved extracting the dry scabs caused by the disease, reducing them to a fine powder and then having the patient inhale the powder through the nose with the aid of a silver tube. Despite the imperfection of such a method, it is undeniable that variolation as practiced in China played a significant role in the prevention of smallpox. It was the earliest vaccination method in the world. Knowledge of the process quickly spread to Europe.

Supplement to the Bencao Gangmu and Plant Therapy

Zhao Xuemin (1719-1805) bequeathed to Chinese medicine and pharmacy a supplement text to the Bencao Gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica), called Bencao Gangmu Shiyi, published in 1765. A total of 921 drugs were listed under the categories of water, fire, earth, metals, stones, herbs, trees, creeping plants, flowers, fruit, seeds, vegetables, utensils, birds, quadrupeds, creatures with scales or shells, and insects.

The most significant feature of Zhao's work, however, was the introduction of medical substances that he had learned to recognize and use while talking with traveling physicians. His book, Chuanya (1759), recorded these teachings. The popularity of such physicians, who were also known as "bell physicians" (lingyi) because they announced their presence by means of a small bell, stemmed from the fact that they prescribed medicinal plants that were accessible and thus inexpensive. Zhao Xuemin thought highly of these physicians (it might be said that the famous "barefoot doctors" of post-1949 China were their heirs), concluding that the drugs they recommended were cheap, efficient and practical. He noted in the book that drugs need not be expensive and berated the medical quacks whose scientific skills did not match their high fees. In his opinion, such people knew how to prescribe an expensive tonic, but did not know how to recognize a medicinal plant.

The traveling herbalist in Qing

(Taken from the Complete Illustrated Guide to Chinese Medicine, 1996 ) |

Typical Chinese dispensary

(Taken from Chinese Herbal Medicine 1986) |

Phytotherapy (plant therapy) remained the basis of Chinese medicine throughout the nineteenth century and earlier medical works of this tradition were reissued in new editions. It was the desire to revive this plant-based medicine that inspired physicians like Wu Qijun (1789-1846), who published Zhiwu Mingshi Tukao (Illustrated Account of Flora), and Fei Boxiong, who published Yichun Shengui in 1863. The best known dispensary of the time, the Tongren tang, was located in the capital Beijing and catered especially to the imperial family.

Publishing Boom in Encyclopedias and Medical Books

Anxious to obtain the support of the scholar class, the new rulers encouraged intellectual life and gave patronage to encyclopedic projects in history, arts, medicine and science.

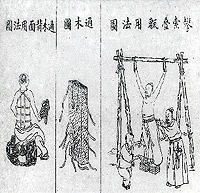

Illustrations from Yizong Jinjian

(Golden Mirror of Medicine)- about bone setting |

The encyclopedia became very popular in the 1700s. One Chinese medicine classic that emerged during this publishing boom was the Gujin Tushu Jicheng (Collection of Ancient and Modern Works), an encyclopedia of 10,000 chapters that provides much background to the history of Chinese medicine. Published in 1726, about 520 chapters of the encyclopedia focused on medicine. Another famous work was the Yizong Jinjian (Golden Mirror of Medicine) written by Wu Qian in 1742. To this day, this remains an important reference book.

A trend also developed of authors writing collections of books. These collections provide windows into the different thoughts of the period. For example, Zhang Lu (1617-1700) wrote Zhangshi Yitong (A Summary of Master Zhang's Medical Thought), which supported the school of warming and invigoration.

At the same time, more modest publications on medicine appeared. They tended to be introductions into Chinese medicine, such as the Yixue Xinwu ( An Understanding of Medicine) published in 1732 by Cheng Guopend. The book discussed the four methods of examination, diagnostic principles and therapeutic techniques that served as the basis of medical training. Another book, Zhengzhi huibu by Li Yongcui, which dates from 1687, is entirely devoted to illnesses and their symptoms that relied on internal medicine for treatment.

The fascination for ancient classics re-emerged during the Qing period and many were re-edited, such as the Huang Di Nei jing (The Yellow Emperor's Medicine Classic), Shanghanlun (Treatise on Febrile Diseases) and Jinkui Yaolue (Summary of the Golden Chest). They enjoyed considerable popularity and were subject to various commentaries.

Other texts written during this dynasty focused on topics such as gynecology, pediatrics, ophthalmology, massage and external medicine, which mainly dealt with skin diseases or trauma.

Rise of Western Medicine

China's internal weaknesses made her vulnerable to Western nations hungry for economic benefit in the later nineteenth century. Christian missionaries and medical doctors associated with the church played a major role in establishing foreign influence in China at this time. This triggered growth in the number of medical schools run by the Chinese, or jointly with Western doctors, and many Western medical books were translated. Chinese doctors at this time were also introduced to Western medical practice. The first Chinese to study medicine abroad was Huang Kuan (1829-1878), a Cantonese who went to Edinburgh University in Scotland, and then disseminated what he had learned on returning to his native Guangzhou. This brought about a new generation of doctors who saw a wealth of knowledge in Western medicine.

A description of ginseng which talks about its properties and functions. Ginseng was an expensive herb even in the Qing Dynasty and hard to come by. |

Integrated Traditional Chinese Medicine

In the late-Qing, this Westernization movement had a significant impact on traditional Chinese medicine. Response to the movement varied: some practitioners refused to accept Western medicine, denying its value completely; some regarded traditional Chinese medicine as non-scientific and argued that it should be banned; and others tried to learn from Western medicine and integrate this knowledge into their traditional practice. One of the earliest pioneers for the integration of Eastern and Western medicine was Zhu Peiwen. His Huayang Zangxiang Yuezuan (A Combining Chinese and Western Anatomy Illustration) of 1892, illustrated organs according to both Chinese and Western concepts. He suggested that each tradition had its advantages and disadvantages. This integrated approach enjoyed little success during the Qing dynasty because of strong adherence to traditional Chinese medicine texts and skepticism about medical knowledge garnered from the West.

|